The Industrial Revolution in Great Britain: 18th-20th Centuries

A Profound Transformation of Technology, Society, and the World

I. Introduction: A Revolution That Changed the Course of History

The Industrial Revolution denotes the profound transformation of technology, society, and economic structures that originated in Great Britain in the mid-18th century before spreading across the globe. This momentous transition from an agrarian, handicraft-based economy to a machine-centric, industrial society liberated humanity from the millennia-long constraints of subsistence agriculture, ushering in an era of unprecedented material abundance and sustained economic growth. This revolution laid the groundwork for the modern capitalist system and marked a historical turning point that permanently altered humanity’s way of life, social structures, and the global order. This report provides a comprehensive examination of the British Industrial Revolution, analyzing its background, development, socio-economic impact, and global influence to elucidate its historical significance and lasting legacy.

II. Main Body: The Engines of Change and Their Consequences

A. Timeline: Key Milestones of the Industrial Revolution

| Date | Technological Innovations | Socio-Economic Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 1712 | Thomas Newcomen invents the atmospheric steam engine. | Early power source for pumping water from coal mines. |

| 1733 | John Kay invents the ‘flying shuttle’. | Doubled weaving speed, creating a bottleneck in yarn production. |

| 1764 | James Hargreaves invents the ‘spinning jenny’. | Initiated the mass production of cotton yarn. |

| 1769 | James Watt patents the separate condenser steam engine. | Revolutionized power generation, becoming a critical turning point for industry. |

| 1776 | Adam Smith publishes *The Wealth of Nations*. | Provided the philosophical basis for free-market capitalism. |

| 1785 | Edmund Cartwright invents the ‘power loom’. | Completed the mechanization of the weaving process. |

| 1811-13 | The Luddite Movement (machine-breaking). | Organized resistance by workers against mechanization. |

| 1825 | The Stockton and Darlington Railway opens. | Launched the railway age and revolutionized logistics. |

| 1830 | The Liverpool and Manchester Railway opens. | Established the first inter-city passenger and freight railway. |

| 1833 | The Factory Act is passed. | First major legislation to regulate child labor. |

| 1851 | The Great Exhibition is held in London. | Showcased Britain’s industrial prowess, solidifying its status as the ‘workshop of the world’. |

| 1914 | Outbreak of World War I. | Signaled the decline of British industrial supremacy and the dawn of a new global era. |

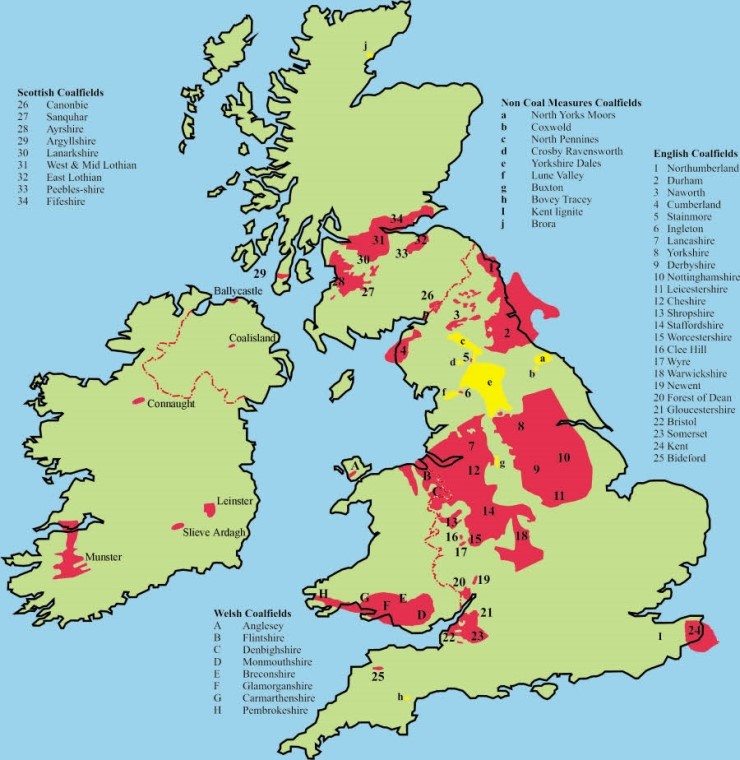

B. Background: Why Great Britain?

Great Britain’s emergence as the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution was not due to a single cause, but a confluence of several advantageous factors. First, the 18th-century Agricultural Revolution boosted food production, which supported population growth and created a surplus labor force available for urban industries. Second, Britain possessed abundant reserves of coal and iron ore—essential industrial resources—and a well-developed transportation network of canals and maritime routes. Third, the accumulation of vast capital from its colonial empire, coupled with a stable financial system anchored by the Bank of England, enabled large-scale investment in new enterprises.

Finally, the political stability established after the Glorious Revolution (1688)—characterized by parliamentary rule, the protection of private property, and a patent system—provided a social framework that encouraged free enterprise and technological innovation. This ethos was underpinned by the economic theories of Adam Smith.

In his seminal work, *The Wealth of Nations* (1776), Adam Smith emphasized the division of labor, arguing that the self-interested economic activities of individuals, guided by an ‘invisible hand,’ ultimately increase the wealth of the entire society. His ideas provided the theoretical foundation for a laissez-faire economic system, becoming the intellectual bedrock for a new industrial capitalism focused on improving productivity and accumulating capital.

C. Development and Technological Innovation: The Inventions That Drove Change

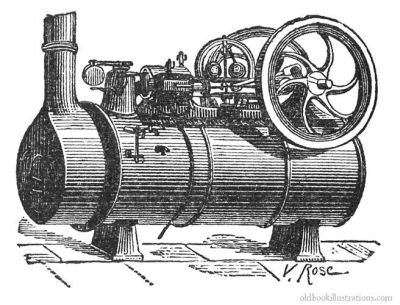

The Industrial Revolution unfolded as a chain reaction of technological advancements, beginning with the cotton textile industry and spreading to power generation with the steam engine, and subsequently to the iron, steel, and transportation sectors. At the heart of these innovations were visionary inventors and decisive entrepreneurs who spearheaded this new era.

1. The Cotton Industry: The Genesis of Innovation

To meet the soaring domestic and international demand for cotton textiles, a series of inventions for spinning and weaving machinery appeared in rapid succession. Innovations, starting with John Kay’s flying shuttle, led to James Hargreaves’s spinning jenny, Richard Arkwright’s water frame, and Samuel Crompton’s spinning mule, which collectively caused an explosive increase in yarn production. This transition from a cottage-based industry to a centralized factory system marked the dawn of mass production.

2. The Steam Engine: The Powerhouse of the Revolution

The steam engine, significantly improved by James Watt from Thomas Newcomen’s earlier design, stands as the most iconic invention of the Industrial Revolution. Unlike the water-powered mills that preceded them, steam engines provided a versatile power source that could be located anywhere with access to coal. This innovation removed geographical constraints on factory placement, dramatically increased production capacity, and catalyzed the spread of industrialization across all sectors.

3. Railways and the Transportation Revolution

The convergence of steam power and advanced iron-making techniques gave rise to the railway. Starting with the Stockton and Darlington Railway in 1825 and the Liverpool-Manchester Railway in 1830, a national network rapidly took shape. Railways enabled the cheap, rapid, and large-scale transport of raw materials and finished goods, integrating the national market and serving as the arteries of the burgeoning capitalist economy.

Key Inventors and Entrepreneurs

The history of the Industrial Revolution is also the story of brilliant and determined individuals. James Watt, a Scottish instrument maker, crucially improved the steam engine by adding a separate condenser, which increased its thermal efficiency more than fivefold. His partnership with entrepreneur Matthew Boulton was vital to commercializing the invention, and Watt also introduced ‘horsepower’ as a standard unit for measuring power.

In the textile industry, Richard Arkwright not only invented the water frame (1769) but is also considered the father of the modern factory system, having established a large water-powered mill that employed hundreds of workers. In the railway sector, George Stephenson developed practical steam locomotives, including ‘Locomotion No. 1’ and the ‘Rocket.’ His work led to the world’s first public railway in 1825 and the first inter-city line in 1830, establishing him as a key figure who revolutionized logistics and transport.

E. Global Impact: A Wave of Change Across the Planet

The wave of industrialization that began in Great Britain soon crossed its borders, spreading throughout the world and fundamentally reshaping the global landscape.

1. The Spread of the Industrial Revolution

Britain’s industrial success served as a powerful catalyst for other nations. From the mid-19th century, industrialization spread across continental Europe—notably to Belgium, France, and Germany—as well as to the United States, and later to Japan and Russia. Each nation entered the industrial race by adapting or imitating the British model to fit its own circumstances.

2. Imperialism and the New Global Economy

Industrial nations embarked on aggressive expansion into non-industrialized regions to secure overseas markets for their mass-produced goods and cheap sources of raw materials. This dynamic intensified imperialist competition in the late 19th century and established an unequal global division of labor, with industrial ‘core’ nations politically and economically dominating non-industrial ‘periphery’ nations. Having become the ‘workshop of the world,’ Great Britain used its powerful navy to build a vast ’empire on which the sun never sets,’ thereby establishing the 19th-century global order known as Pax Britannica.

III. Conclusion: Legacy and Modern Reflections

The Industrial Revolution was a pivotal historical event that liberated humanity from the long-standing constraints of agrarian society. It ushered in an era of material abundance and sustained economic growth, forming the foundational framework of modern society, including capitalism, urbanization, and our contemporary class structure. Its undeniable positive legacies include the acceleration of technological progress, long-term improvements in living standards, and the democratization of consumption through mass production.

However, this progress cast a long shadow, sowing the seeds of problems that persist today: extreme wealth inequality, labor alienation, environmental degradation, and an ideology used to justify imperialist aggression. Just as past innovations created modern challenges, we who live in the age of a Fourth Industrial Revolution must reflect deeply on the light and shadow that new technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) and automation will cast upon our future. The history of the Industrial Revolution teaches a crucial lesson: that more important than technology itself is the social and institutional commitment to anticipate its impacts, mitigate its negative consequences, and strive for inclusive growth for all members of society.

IV. References

This report was compiled using information from authoritative academic sources, scholarly encyclopedias, and specialized history websites.

- Britannica. “Industrial Revolution”, “Social Change in the British Industrial Revolution”, “Inventors and Inventions of the Industrial Revolution”.

- World History Encyclopedia. “The Impact of the British Industrial Revolution”, “Social Change in the British Industrial Revolution”.

- HISTORY. “Industrial Revolution: Definition, Inventions & Dates”.

- Khan Academy. “READ: The Global Transformations of the Industrial Revolution”.

- Hobsbawm, Eric. *The Age of Revolution: 1789-1848*. Vintage, 1996.

- Landes, David S. *The Unbound Prometheus: Technological Change and Industrial Development in Western Europe from 1750 to the Present*. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Engels, Friedrich. *The Condition of the Working Class in England*. 1845.

- Image Sources: Britannica, World History Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Commons, National Archives, etc.

D. Socio-Economic Changes: The Light and Shadow of Progress

The Industrial Revolution was more than a mere change in production methods; it fundamentally reshaped British society and every aspect of human life. The advance of the capitalist economy and unprecedented urbanization gave rise to acute social problems and class conflict.

1. New Social Classes and the Labor Movement

Society was increasingly defined by two new classes: the industrial capitalists (bourgeoisie), who owned the means of production like factories and capital, and the industrial workers (proletariat), who sold their labor for wages. Workers endured grueling conditions: long hours (typically 12 to 16 per day), low wages that barely provided for subsistence, and dangerous, unsanitary environments. The exploitation of female and child labor was a particularly dark facet of this era.

These harsh conditions inevitably led to collective resistance from workers. The Luddite Movement (1811–1813), in which textile workers displaced by mechanization destroyed machinery to protest their loss of livelihood, was a prominent early form of resistance. Subsequently, workers began to form trade unions to systematically demand higher wages and better working conditions. These struggles led to gradual reforms, such as the Factory Act of 1833, which placed the first legal limits on child labor. Social reformers like Robert Owen sought to create national unions to protect workers’ rights, thereby broadening the scope of the labor movement.

2. Rapid Urbanization and Environmental Degradation

Industrial cities like Manchester, Liverpool, and Birmingham expanded rapidly, resulting in massive population concentrations. By 1851, Britain had become the first nation in history where the urban population surpassed the rural population. However, this rapid, unplanned urbanization created severe problems. Housing was cramped and sanitation was inadequate, with poor sewage systems leading to recurrent outbreaks of waterborne diseases like cholera. Smoke from factories polluted the air, creating the new term ‘smog,’ while industrial effluent turned rivers into lifeless channels. These dismal urban and environmental conditions contributed to lower life expectancies for the working class. The Public Health Act of 1848 marked the first significant government intervention aimed at systematically addressing urban sanitation and environmental issues.

3. Transformation of Social Structure

The Industrial Revolution profoundly altered the structure of British society. The traditional hierarchy, centered on the landed aristocracy, weakened as the newly wealthy industrial bourgeoisie emerged as the dominant social and economic force. The old community-based agrarian society dissolved, replaced by a new urban society where individuals and nuclear families became the primary social units. In this process, the class divide between the bourgeoisie, owners of the means of production, and the proletariat, who possessed only their labor, widened and became deeply entrenched. This new class structure became a central subject of analysis for contemporary intellectuals.